The life of Napoleon Bonaparte, remembered as one of history’s greatest conquerors, shares countless parallels with that of Julius Caesar. Fueled by a profound admiration for the classics, Napoleon, and subsequently his nephew Napoleon III, explicitly modeled their political and military achievements on those of the mighty Roman general. These connections offer fascinating insights into the enduring influence of classical antiquity on the shaping of modern history.

Napoleon I in Coronation Robes by François Gérard, 1805. (Public domain)

The Legacy of Caesarism: From Ancient Rome to Revolutionary France

The term “Caesarism” denotes a form of government led by a dictator. The original Julius Caesar, a pivotal figure in the final era of the Late Roman Republic, emerged during a tumultuous period when Rome’s governance teetered on the brink of collapse, notably around the mid-1st century BC. Faced with the aftermath of a devastating civil war, Caesar assumed control to restore order, establishing himself as Rome’s dictator for life. Invoking Caesar’s example, Napoleon Bonaparte—a famed military leader who later became Emperor of France in the early 19th century—did the same thing for post-Revolutionary France.

Both men presented themselves as the “true” defender of the Republic. For Caesar, he saw himself as a populist against the aristocratic privileges of the Senate. In Napoleon’s case, he sought to protect the French Republic from an imminent invasion by the European Allies, who were conspiring to reinstall the Bourbon monarchy.

Drawing connections to ancient Rome, Napoleon styled himself as the First Consul of France. But just like the triumvirates of the Late Republic, Bonaparte skillfully outmaneuvered the other consuls, leaving him as the de facto strongman of France.

The politics of Napoleon became formalized into the ideology of Bonapartism, a term used to refer to the rule of a military dictator who legitimizes his policies by holding direct votes to the public, called plebiscites. This transformation was especially pronounced during the reign of his nephew, Emperor Napoleon III.

Like Caesar before him, the third Napoleon—who was Emperor of France from 1852 to 1870—enjoyed great popularity among the poor people of France. Napoleon III styled himself as a Caesar-like figure, invoking the military prestige of the ancient Roman conqueror. His coup d’état against the French government in 1851 was codenamed Operation Rubicon, in reference to Caesar’s march on Rome.

Following Caesar’s example, Napoleon III presented himself as the “true” man of the people, a dictator committed to safeguarding the interests of the disenfranchised working class. Together, the rule of the two Napoleons inspired an ideology of enlightened dictatorship, a type of political Caesarism which still influences governments around the world.

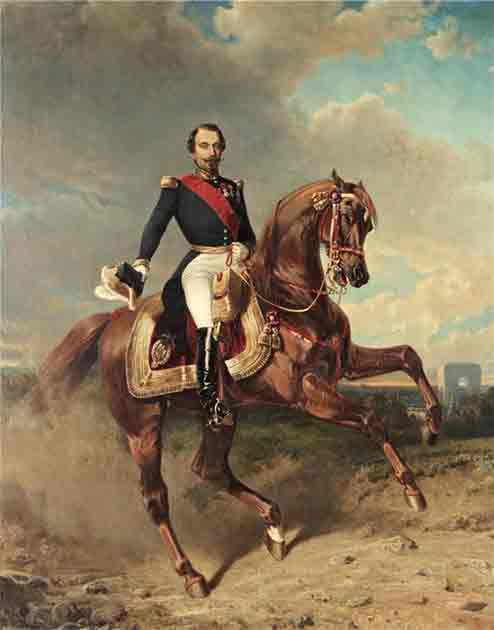

Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, by Carl Frederik Kiörboe. (Public domain)

Napoleon’s Alpine Odyssey: Echoes of Hannibal’s Legendary Invasion

Napoleon praised Caesar as a triumphant leader, who unified Europe through his grand conquests. Just like his Roman hero, Bonaparte came from a family of Italian minor nobles. Caesar boasted of his conquests in places like Gaul and Britannia, while Napoleon’s military victories stretched across the European continent. Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul took place in what is now France, a fact that was almost certainly not lost on a French nationalist like Napoleon.

In 1796, France sent General Bonaparte to conquer his ancestral homeland from the Austrians. At first, the French military dismissed the Little Corporeal—a dismissive nickname given to General Bonaparte by members of the French military—mocking him as a starry-eyed upstart from Corsica.

For almost two years, the French Army had been stalled in the foothills of the Italian Alps. “Soldiers, you are naked and ill-fed. No fame shines upon you,” the charismatic Napoleon told his men. “I will lead you into the most fertile plains in the world. Rich provinces, great cities will line in your power. You will find there honor, glory, and riches!” he boldly promised them.

It was all the more enthralling, since the French soldiers were hopelessly outnumbered 38,000 to 63,000 men. In just two weeks, Napoleon won six battles and took thousands of prisoners. The myth of Napoleon was born!

Napoleon made a second campaign into Italy in 1800. His famous crossing over the Alps was immortalized by a French painter named Jacques-Louis David. It was inspired by Hannibal’s invasion of Italy during the Second Punic War. Having successfully subduing the Austrians, he looted Italy of its artistic treasures. This included many priceless artworks from Classical Antiquity and the Renaissance.

Napoleon Bonaparte Crossing the Alps, by Jacques-Louis David. (Public domain)

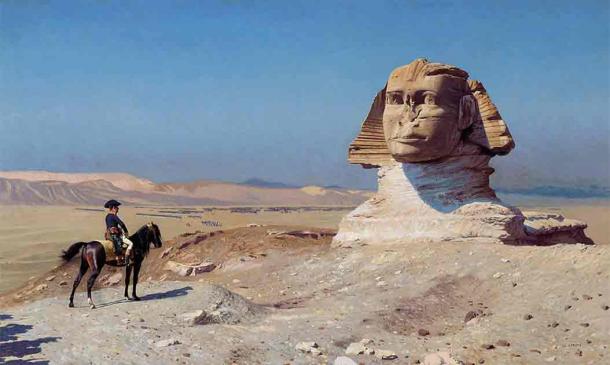

Napoleon’s Egyptian Expedition and the Birth of Egyptology

For anybody who loves classics, we can thank Napoleon for our modern knowledge about ancient Egypt. In 1798, amidst political turmoil in France, the Directory—France’s new democratic government—faced mounting pressure from Britain to dismantle the gains of the French Revolution. In response, they turned to the ambitious 28-year-old artillery officer, Napoleon, summoning him for a daring expedition into Egypt.

Just as in Caesar’s day, Egypt represented the nexus between East and West. By invading Egypt, the French would challenge British colonial presence in India. The French also wanted to compensate their sugar trade, after losing their colony of Haiti. Beyond material reasons, the French wanted to spread the ideas of the Enlightenment, which was heavily influenced by the classical civilizations of Greece, Rome and Egypt. The French soldiers frequently compared themselves to the Roman legions of Caesar and Octavian.

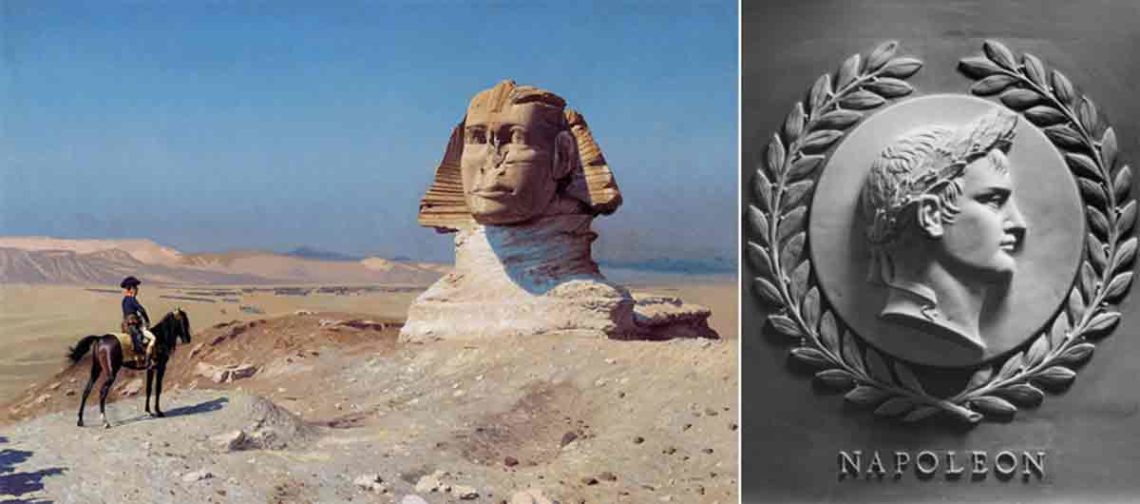

Napoleon Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. (Public domain)

On July 1, Napoleon and his French troops arrived in Alexandria. Now in Muslim territory, General Bonaparte instructed his men to respect the culture of Egypt. Following his pagan predecessors, Napoleon argued that the Roman legions had once protected all religions; he urged his own French troops to do likewise. He did not seek impose Europe’s Christianity on the Muslims. He syncretized parts of Islam into his own spiritual beliefs—a very Roman thing to do! Thus, for Napoleon, the pagan Caesar was a symbol of religious tolerance and respect for Cairo’s culture.

But the French were shocked to find that the Muslim Egyptians had completely forgotten their classical heritage! Given Egypt’s rich classical history, the French were initially disappointed to find themselves in the very poorest part of the Ottoman Empire. All they could find was an obelisk to the great Cleopatra, the exotic lover of Caesar and Mark Antony nearly two millennia before. Napoleon knew very well how Octavian had seized power as Rome’s emperor after defeating Mark Antony and his Egyptian consort at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

For our French Caesar, the Cleopatra story would have held a very personal significance. While away on his campaign in Egypt, Napoleon was horrified by the news of his wife’s extramarital affair back in Paris. Seeking revenge, the wounded Frenchman took a mistress by the name of Pauline Fourès, who became known as “Bonaparte’s Cleopatra.”

Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt marked a turning point for classical studies. With the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, the French Caesar facilitated the unraveling of the mysteries of the Orient. This breakthrough enabled European scholars to decipher hieroglyphs, paving the way for the birth of the modern field of Egyptology.

Top image: Left; Napoleon Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, by Jean-Léon Gérôme. Right; Bas-relief of Napoleon Bonaparte Emperor of France in the chamber of the United States House of Representatives. Source: Left; Public domain, Right; Public domain

By Ben Shehadi

Ben Shedadi’s latest book, The Revolutionary Hero, is a 200-page biography of Napoleon Bonaparte. In it, he talks about Napoleon’s early life, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. It is available now on Amazon; on Kindle ($3.99) and Paperback ($19.99): https://a.co/d/9YDy0We Ben Shedadi has more articles on Napolean on Substack: https://hothistory.substack.com/t/napoleon