Thanks to Joseph Goebbels, the film director Georg Wilhelm Pabst luxuriated in a massive budget for the dramatised documentary he shot in occupied Prague during the autumn of 1942. Commissioned to celebrate the long history of Germanic culture, its central character was a 16th-century demagogue, a revisionary doctor who toured the country inciting enthusiastic crowds to dispense with conventional practices and adopt his own inspiring visions for a utopian future.

The starring role was played by Werner Krauss, a fine actor but also a fervent Nazi supporter. Bearing only a loose relationship to historical fact, the plot revolved around attempts to ward off an infectious plague – or, metaphorically, to cleanse society of undesirable parasites. A clear piece of propaganda, Pabst’s Paracelsus was a box-office flop, although – in contrast with Krauss – the director managed to salvage his reputation after the Third Reich collapsed.

Becoming Paracelsus

The real Paracelsus (c.1493-1541) was, indeed, an unorthodox and controversial physician, a confrontational iconoclast only later glorified for introducing modern medical techniques. Depending on which artist you believe, he may (or may not) have been fat, but he certainly had a substantial name: Theophrastus Philippus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim. Ironically, the original Theophrastus had been the immediate successor of Aristotle, one of the ancient Greek authorities the Renaissance radical was determined to overthrow.

Refashioned as Paracelsus, he excelled at rhetorical oratory, winning popular acclaim by using vernacular language to lambast the tortuous prose of conventional experts. Recalling Martin Luther’s flamboyant gesture, on St John’s Day (24 June) 1527 he threw a collection of canonical books onto a public bonfire. ‘I tell you’, he ranted to a scholarly audience, ‘one hair on my neck knows more than all you authors, and my shoe-buckles contain more wisdom than both Galen and Avicenna.’ In one fell swoop, Paracelsus had dismissed two of Europe’s reigning medical authorities.

Consistency was not his strong point: this showman who publicly consigned books to the flames was himself a prodigious author. Openly contemptuous of scholarly learning – ‘not even a dog-killer can learn his trade from books’ – he wrote copiously about the importance of abandoning libraries to learn from the great ‘Book of Nature’. Only a small proportion of his output was published during his lifetime, but his ideas spread rapidly and 50 years after his death the first collection of his works ran to ten volumes. Another favourite theme was to boast about his humble origins and plebeian influences – ‘I have not been ashamed to learn from tramps, butchers and barbers’ – even though he had benefited from a sound education as a child and gained a doctorate in medicine from the University of Ferrara.

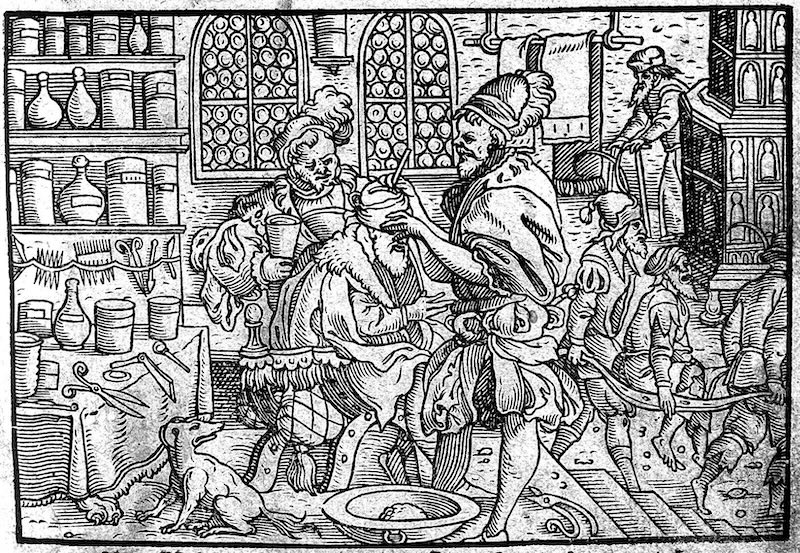

As a young man, Paracelsus travelled around Europe for several years before falling into a pattern of behaviour that repeated itself for the rest of his life. Wherever he temporarily took up residence, he baited his fellow academics by donning an alchemist’s leather apron to lecture in German rather than Latin, as well as deliberately insulting recognised experts, vociferously condemning orthodox treatments and acquiring a reputation for drunkenness and gluttony. As a consequence, every time he established himself as a professor or physician – first at Basel, then at Nuremberg and elsewhere – he rapidly antagonised his colleagues and was forced to move on.

Chemical cure

According to the views of the time, each individual body is characterised by its own finely tuned balance of four different humours that affect behaviour as well as appearance: sickness results not from invasion by germs, but from an internal humoral imbalance. Doctors therefore emphasised the importance of restoring a patient’s natural equilibrium. In the absence of antibiotics or anaesthetics, they proceeded cautiously, their most frequent interventions being to let blood or smell urine.

Paracelsus, in contrast, taught that external agents could produce specific disorders. For example, gout – one of the period’s more common maladies – was routinely attributed to a surplus of humoral fluid, but Paracelsus regarded it as a dietary disease. Bragging about the low incidence of gout in his native Switzerland (according to his characteristically overblown rhetoric, the country was ‘superior to … all Western and Eastern Europe’), he suggested that salts in the water supply were coagulating inside the joints to produce painful nodules resembling gallstones or dental tartar.

Paracelsus’ main innovation was to prescribe chemical treatments. Although that might sound like a precursor of modern medicine, it was rooted in ancient alchemical lore. Alchemists deliberately couched their precepts in arcane mystical terms, both to protect their techniques from being copied and to preserve their aura of esoteric superiority; as a result, many of Paracelsus’ ideas defy easy interpretation. Fundamentally, he maintained that there are three primary idealised principles corresponding to different aspects of existence. Confusingly, the members of this ‘tria prima’ are referred to as salt, sulphur and mercury, which, although different from the physical substances carrying the same labels, can imbue metals and minerals with therapeutic or poisonous qualities.

Paracelsus is frequently celebrated as the ‘father of toxicology’ because he recognised the principle that the same substance can have either deleterious or beneficial effects, depending on the quantity imbibed – or, as he put it: ‘Solely the dose determines that a thing is not a poison.’ Some of his other recommendations are preserved in modern medical practices, although these are often picked out selectively to give him more credit than he merits. Thus he insisted that wounds should be kept clean rather than covered in cow dung or feathers, and he provided recipes for various liniments and skin balms. After studying syphilis, he concluded that it could be inherited or acquired through contact, and his prescription of mercury was still being used in the 20th century. Often said to have introduced opium into Europe, he also suggested that iron was beneficial for blood and endorsed drinking water from mineral springs.

The doctrine of signatures

Like many self-professed revolutionaries, Paracelsus was less radical than he claimed. In particular, he endorsed an ancient religious philosophy known as ‘the doctrine of signatures’, which maintained that God had coded the natural world with symbols so that it could be interpreted for human benefit. Plants that resembled parts of the body could be used therapeutically: ‘Nature marks each growth … according to its curative benefit’, he declared.

St John’s Wort, for instance, was recommended for dermatological complaints, because its leaves are punctured with little holes like the pores of the skin, while the large growths of tree fungi were prescribed for tumours. Some vernacular names of plants still convey their herbal significance, such as eyebright (euphrasia), traditionally used for soothing conjunctivitis because the flowers look like blue eyes. Even some Latinised Linnean labels carry this cultural memory, including toothwort (dentaria) and lungwort (pulmonaria); conversely, orchitis – inflammation of the testicles – gained its name from the shape of orchid roots, which were used to treat venereal diseases and improve potency.

Regarded superficially, the doctrine of signatures can be made to sound ridiculous. Taken more seriously, it expressed a profound faith in a universe imbued with God’s intentions. Philosophically, it played on the close interaction of the microcosm and the macrocosm, the view that the very small has similar characteristics to the larger structure in which it is embedded. Thus the human body was often said to be the microcosm of the universe, while Isaac Newton professed that the dimensions of King Solomon’s temple as deduced from biblical sources would guide him towards God’s blueprint for the macrocosm of creation.

Look for yourself

Paracelsus stressed that a successful physician must lead a virtuous life and pray for God’s guidance in searching out divine signs in the world. Close observation was of paramount importance, whether deciphering the symbolic language of the plants or tracking the course of an illness. ‘The patients are your text book, the sickbed is your study’, he admonished his rivals.

Just two years after Paracelsus died Andreas Vesalius – the most famous anatomist of the Renaissance – delivered the same message through his extraordinary drawings. Until then, students had learnt about the human body by listening to professors as they read aloud from books perpetuating ideas that were more than 1,000 years old. Like Paracelsus, Vesalius insisted that for physicians of the future, the way forward lay in looking for themselves and learning from their experience.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her most recent book is Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2021).