Hungry for power, in 1798 Napoleon sailed off across the Mediterranean, backed by a contingent of 50,000 military men and 151 scholarly volunteers. Napoleon’s critics denounced this mission as an expensive, ill-judged attempt to compete with British global expansion by colonising part of northern Africa. But for those in the academic contingent, his initiative represented a thrilling opportunity. Pursued by Horatio Nelson’s British fleet, they spent 30 days on the emperor’s ship before disembarking in Alexandria.

During the next three years, this diverse group of researchers investigated every aspect of Egyptian civilisation they could uncover. Even though around a quarter of them died within the next few years, from their perspective Napoleon’s expedition yielded detailed information about a land virtually unknown to Europeans. In contrast, the disillusioned troops complained bitterly about the heat and the squalor, about the dangers from disease and hostile inhabitants, about the civilians who consumed scarce supplies without contributing anything useful.

Eventually, the French army surrendered, and the Egyptian artefacts they had purloined were classified as spoils of war. One of the most magnificent, the Rosetta Stone, was conveyed to Portsmouth on a captured French frigate and ended up in the British Museum. But an equally extraordinary object known as the Dendera Zodiac had been deliberately left in its original position to save it from being seized by the British.

A couple of decades later, this massive carving was ripped away from its surroundings and despatched to the Louvre. Now Paris boasted its own prize trophy – but the Dendera Zodiac became the focus of a bitter debate. Self-styled experts were divided. Many of them insisted that this antiquity was many thousands of years old. Ranged against them were biblical experts: how, they protested, could Egyptian civilisation predate the earth’s creation in 4004 bc?

France’s Elgin Marbles?

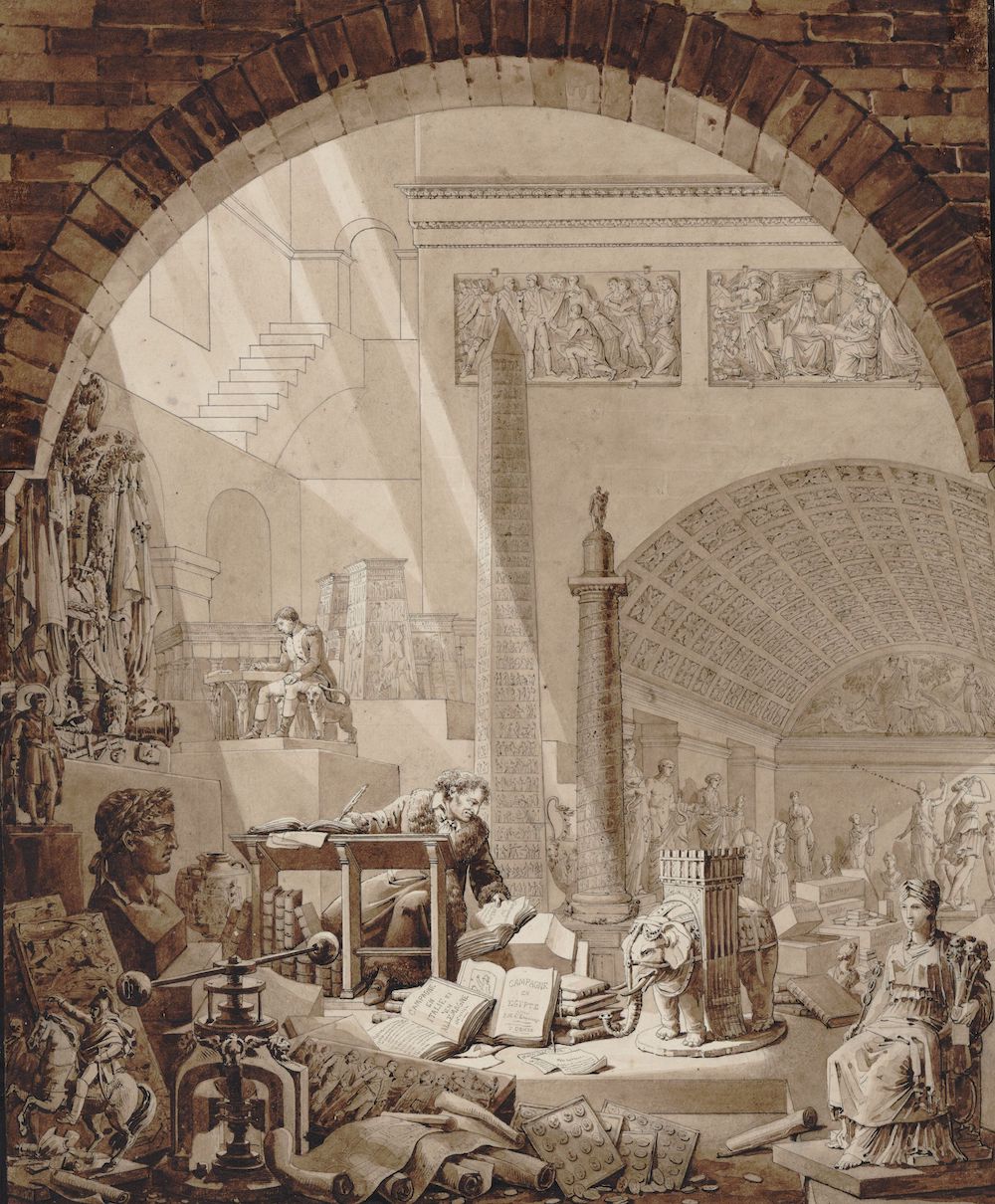

The Zodiac was initially discovered by the artist Dominique-Vivant Denon, who had spotted the massive disc embedded in the ceiling of a ruined temple near Thebes (Luxor). Getting inside required squirming through a tiny window and dropping down into the dark, smelly interior littered with rotting and mummified corpses. By the flickering light of flaming torches, Denon and the men who followed him gazed in amazement at the walls decorated with colourful carvings. They were particularly awed by the ceiling of a small roof chapel, which carried an elaborate sculpted circle supported by goddesses and mythical creatures. Denon made a drawing on the spot, but more accurate renditions were later created by two young engineers who spent several weeks systematically measuring and copying the entire ceiling on a scale of one to five. When they ran out of pencils, they melted down lead bullets, using reeds to cast suitable drawing utensils.

Denon’s two-volume illustrated book of his Egyptian discoveries proved a bestseller across Europe, and obsession with Egypt escalated. As collectors vied to retrieve additional antiquities, they benefited from the Egyptian government’s policy of attracting foreign money by encouraging visitors to tour the country and remove transportable objects for display in prestigious museums and private collections.

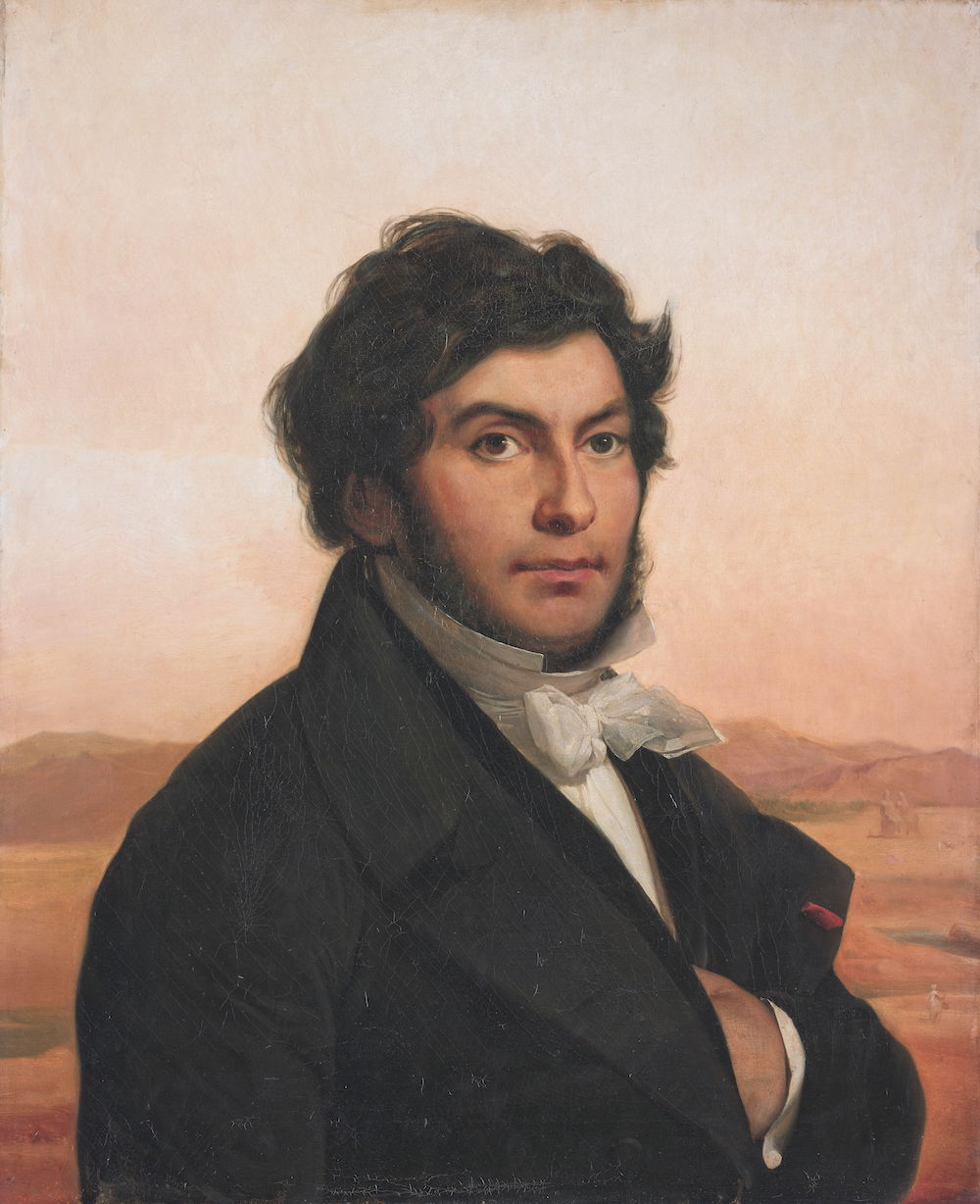

French enthusiasts were especially keen on seizing the Zodiac, which is still the only circular representation of Egyptian astronomy to have been unearthed. Eventually, an excavation team entered the site in 1821 and blasted the disc out of the ceiling. Virtually the only French protest was expressed anonymously by a philologist called Jean-François Champollion, later celebrated for cracking the Rosetta Stone. Professing himself delighted that the Zodiac would be on show next to the Seine rather than the Thames, he asked rhetorically ‘Should we, in France, follow the example of Lord Elgin? Certainly not.’ He thought the Zodiac should have been left near the Nile.

Signs of the Zodiac

When France’s Egyptian trophy landed in Marseilles, crowds gathered along the 500-mile route to Paris, but its triumphant arrival soon exploded into controversy. Paris’ leading experts were intrigued by the novel challenge of deciding what was depicted by the panel’s elaborate carvings. Originally brightly coloured, they displayed the 12 zodiac signs arranged in a circle to represent an Egyptian year of 360 days. One of the first steps was to reconcile Egyptian and European astrological symbolism. For example, two crocodiles swimming in opposite directions correlated with the fish of Pisces; similarly, the ram of Aries corresponded with ram-headed Amun, while Taurus matched Osiris, sometimes known as ‘the bull of eternity’.

One question was fundamental: how old was the disc? The controversy even found its way into an extraordinary vaudeville play that featured a choir of singing mummies providing background music for the dramatic action between Osiris, Mercury and Scorpion. The dialogue limped, but the central issue was clearly spelled out: ‘One scholar says the Zodiac’s of recent vintage / Another, just as smart, / Affirms for those who wonder, / That the world is even younger.’

One of France’s leading Egyptologists horrified non-experts – including the pope and Louis XVIII – by suggesting that the Zodiac dated to around 15,000 bc. Astronomers and mathematicians entered the fray to pronounce upon the configurations of the sun and the stars. Joseph Fourier is now famous for the scientific equations that bear his name, but two centuries ago he was prominent in the world of Egyptologists. He had travelled to Egypt with Napoleon and now he consolidated the national uproar by confirming the Zodiac’s great antiquity.

For devout Christians, this was a sacrilegious suggestion, because it contradicted their belief based on biblical numerology that the earth had been created about 6,000 years ago. They too claimed scientific backing: one astronomer posited a date of 747 bc. To his great dismay, Champollion – a confirmed atheist – found himself being recruited by the scriptural exegetes. Although he insisted that Egyptian culture went back long before the purported date of creation, he maintained that the Zodiac itself had originated only a couple of thousand years ago; according to him, it was of Greek or Roman origin and had been made long after the reign of the pharaohs.

Cartouché!

Champollion was no astronomical mathematician but instead concentrated on the style and meaning of the Zodiac’s symbols. He clinched his case by referring to the drawings of Denon’s two younger colleagues, the engineers who had scrutinised the temple’s surrounding stonework so closely. One of their images showed a goddess’ feet flanked on either side by two ovals of the type reserved for the names of Egyptian royalty (dubbed ‘cartouches’ by the French because their shape recalled cartridge cases). After deciphering the written signs inside these cartouches, Champollion declared that one of them was the Greek word autocrator – thus placing the Zodiac in a later era and proving that it fell well within the 6,000 years permitted by biblical analysis.

Suddenly Champollion found himself in the headlines as the champion of what he regarded as the wrong side of the contest. Summoned to the Vatican, he was congratulated for his defence of orthodox religion by the arch-conservative Leo XII, who invited him to become a cardinal in recognition of his services to the Catholic Church.

Right and wrong

Champollion declined, but his international reputation soared. By 1828, he had been appointed head of the Egyptian department at the Louvre, and he decided to visit the temple at Dendera and see it with his own eyes. He spent his first evening in the desert gazing rapturously at the building’s profile in the light of a nearly full moon. Early the next morning he stripped down to his underwear and crawled on his stomach through the sand blocking the entrance. The air inside felt like a furnace. Just as he had anticipated, there was a large gap in the ceiling where French plunderers had removed the plaque and taken it back to Paris.

For the rest of his life, what happened next remained a closely guarded secret between Champollion and his elder brother. As he gazed at the remaining inscriptions, he realised that all the cartouches were empty – and that included the one supposedly carrying the crucial word autocrator. Champollion had unwittingly been putting forward false arguments that strengthened the position of his opponents.

It remains unclear whether the perpetrators of this error simply made a mistake or intentionally faked the evidence. Even so, Champollion has since been vindicated: the Zodiac is now believed to have been created in the first century bc during the reign of Cleopatra VII, just before Egypt was absorbed into the Roman Empire. Champollion had been right – but for the wrong reasons.

Patricia Fara is an Emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge. Her most recent book is Life after Gravity: The London Career of Isaac Newton (Oxford University Press, 2021).