Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – In 2023, scientists presented several interesting studies that gave us a better knowledge of our ancient human ancestors. In this article, we selected ten of the most fascinating finds.

Homo neanderthalensis cranium from the Tabun Cave Israel. Credit: NhM – Right: Tabun Cave, Israel. Credit: Greg Schechter – CC BY 2.0

New dating analysis of existing human remains found worldwide has raised questions about some of our current histories of human evolution.

The existence of early Homo sapiens in Europe was over 150,000 years earlier than first thought.

The application of modern dating methods to fossil human remains has catalyzed major revisions in our understanding of human evolution. In a new review published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews, Rainer Grün of the Australian National University in Canberra and Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum, London, show how the reanalysis of fossils discovered across the world brings into question our current ideas of human evolution, some of which may be incorrect. Read more here

A computer reconstruction of the skull and jaw fragments unearthed in China. New fossil fragments suggest the skull could have come from an unknown human lineage. (Image credit: See Eurekalert (2019))

There may still be vanished human species unknown to scientists. A research team has discovered an unusual 300,000-year-old jawbone with an unexpected combination of archaic and modern human features.

The ancient human jawbone, unearthed by anthropologists in China, belonged to a young teenager. “Given its late Middle Pleistocene age and differs from approximately contemporaneous Homo members such as Xujiayao, Penghu, and Xiahe. This mosaic pattern has never been recorded in late Middle Pleistocene hominin fossil assemblages in East Asia,” the researchers write in their study published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

The fossil traits are open to interpretation, and scientists do not want to jump to conclusions. It could be quite possible the currently unknown individual is related toHomo sapiens or our close human relatives. Read more here

Credit: Adobe Stock – Volodymyr

Contemporary humans carry in their cells a small amount of DNA derived from Neanderthals and Denisovans. “Denny,” a 90,000-year-old fossil individual, recently identified as the daughter of a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother, bears testimony to the possibility that interbreeding was quite common among early human species. But when, where, and at what frequency did this interbreeding take place?

In a recent study published in Science , researchers from Korea and Italy have joined hands to answer this question. Using fossil data, supercomputer simulations of past climate, and insights obtained from genomic evidence, the team was able to identify habitat overlaps and contact hotspots of these early human species.

Dr. Jiaoyang Ruan, Postdoctoral Researcher at IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP), South Korea, explains, “Little is known about when, where, and how frequently Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred throughout their shared history. As such, we tried to understand the potential for Neanderthal-Denisovan admixture using species distribution models that bring extensive fossil, archeological, and genetic data together with transient Coupled General Circulation Model simulations of global climate and biome.”

The researchers found that Neanderthals and Denisovans had different environmental preferences to start with. While Denisovans were much more adapted to colder environments, such as the boreal forests and the tundra region in northeastern Eurasia, their Neanderthal cousins preferred the warmer temperate forests and grasslands in the southwest. Read more here

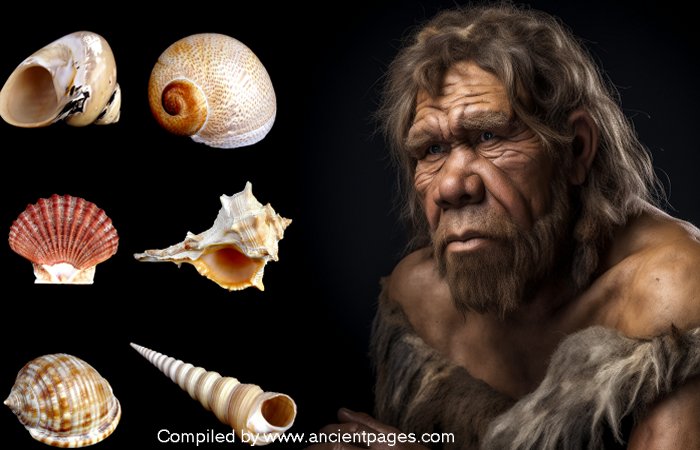

Scientists have found evidence suggesting the ancient use of ochre in Africa and Europe indicates that body painting, clothing decoration, and tattooing may date back to more than 300,00 years ago, or perhaps even 500,000 years ago. But when did our ancestors start showing signs of the early creation of personal identity?

According to scientists, early ancestors collected eye-catching shells that radically changed the way we looked at ourselves and others. A new study confirms previous scant evidence and supports a multistep evolutionary scenario for the culturalization of the human body. Read more here

Recent research has shown that engravings in a cave in La Roche-Cotard (France), which has been sealed for thousands of years, were actually made by Neanderthals.

This research was performed by Basel archaeologist Dorota Wojtczak together with a team of researchers from France and Denmark, whose findings reveal that the Neanderthals were in fact the first humans with an appreciation of art. Read more here

Neanderthal foraging for berries and edible plants in a dense forest. Credit: Adobe Stock – Microgen

Depending upon how you do the counting, there are around 9 million species on Earth, from the simplest single-celled organisms to humans.

It’s reassuring to imagine that complex bodies and brains like ours are the inevitable consequence of evolution, as if evolution had a goal. Unfortunately for human egos, a recent study comparing over a thousand mammals – the group we belong to – painted a less gratifying picture. Read more here

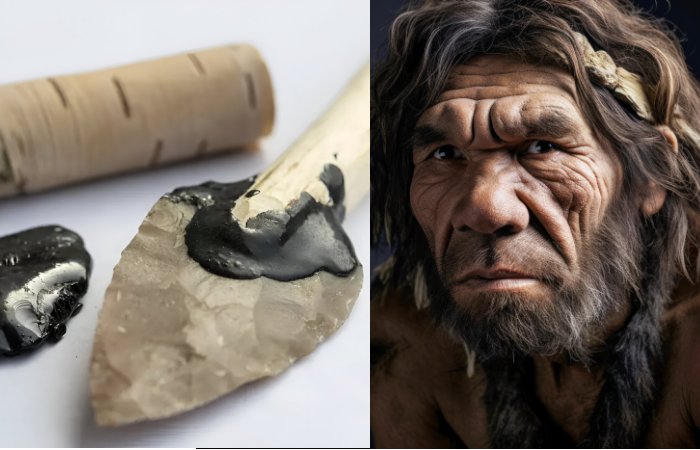

Left: Reproduction of a stone tool hafted to a wooden handle with birch bark tar adhesive Credit: Delft University of Technology – Right: Credit: Adobe Stock – Karrrtinki

Previous studies show Neanderthals invented or developed birch tar making technique independently from Homo sapiens.

Studying prehistoric production processes of birch bark tar using computational modeling reveals the kinds of cognition that were required for the materials produced by Neanderthal and early modern humans.

Birch bark tar is the first time we see evidence of creating a new material, said Dr. Paul Kozowyk, lead author on one of the papers. Examining the methods used to create the tar is an important step in understanding the behaviors and technical cognition required by the Neanderthals. Read more here

Long before the invention of agriculture, humans already knew how to process cereals and other wild plants into a flour suitable for food—and now there’s new evidence they did so long before scientists previously thought.

Published in Quaternary Science Reviews, an Italian-led study of five ancient grindstones from around 39,000 to 43,000 years ago shows that milling for food dates back to the transitional period between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Read more here

The oldest known footprint of our species, lightly ringed with chalk. It appears long and narrow because the trackmaker dragged their heel.Credit: Charles Helm

Just over two decades ago, as the new millennium began, it seemed that tracks left by our ancient human ancestors dating back more than about 50,000 years were excessively rare.

Only four sites had been reported in the whole of Africa at that time. Two were from East Africa: Laetoli in Tanzania and Koobi Fora in Kenya; two were from South Africa (Nahoon and Langebaan). In fact the Nahoon site, reported in 1966, was the first hominin tracksite ever to be described.

In 2023 the situation is very different. It appears that people were not looking hard enough or were not looking in the right places. Today the African tally for dated hominin ichnosites (a term that includes both tracks and other traces) older than 50,000 years stands at 14. These can conveniently be divided into an East African cluster (five sites) and a South African cluster from the Cape coast (nine sites). There are a further ten sites elsewhere in the world including the UK and the Arabian Peninsula.

Given that relatively few skeletal hominin remains have been found on the Cape coast, the traces left by our human ancestors as they moved about ancient landscapes are a useful way to complement and enhance our understanding of ancient hominins in Africa. Read more here

Modern human and archaic Neanderthal skulls side by side, showing difference in nasal height. Credit: Dr Kaustubh Adhikari, UCL

Humans inherited genetic material from Neanderthals that affects the shape of our noses, finds a new study led by UCL researchers.

The new Communications Biology study finds that a particular gene, which leads to a taller nose (from top to bottom), may have been the product of natural selection as ancient humans adapted to colder climates after leaving Africa.

Co-corresponding author Dr. Kaustubh Adhikari (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment and The Open University) said, “In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced, we have been able to learn that our own ancestors apparently interbred with Neanderthals, leaving us with little bits of their DNA.

“Here, we find that some DNA inherited from Neanderthals influences the shape of our faces. This could have been helpful to our ancestors, as it has been passed down for thousands of generations.” Read more here

Written by Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com Staff Writer